Here is one for lovers of crime fiction – a more mature read for senior students and adults. ‘The Ruin’ is the first novel for Irish-born author Dervla McTiernan – the first of (now) several books centred on Garda Cormac Reilly.

Here is one for lovers of crime fiction – a more mature read for senior students and adults. ‘The Ruin’ is the first novel for Irish-born author Dervla McTiernan – the first of (now) several books centred on Garda Cormac Reilly.

Set mainly in Galway (which was actually Dervla’s hometown), it links together a 20-year-old cold case and an apparent suicide. Since his move from Dublin where he was a well-recognised investigator, Detective Reilly has sadly been given yet another cold case to sort through. However, this one has him intricately involved, as it follows up one of his first cases as a rookie police officer.

The prologue tells of Cormac’s first encounter with Maude, Jack and their dead mother in a crumbling country house. Then, 20 years later, he investigates what happened to Maude and Jack after their mother’s death and so the story begins.

In Galway, Cormac’s situation in his new office environment is fraught with all the difficulties of a newbie fitting into the local situation; especially with little recognition of his past professional achievements.

Maude arrives on the scene, attending her brother Jack’s funeral, and seeks to understand why he died. Aislyn, his partner, is also reluctant to believe that Jack was suicidal. Are their instincts correct?

There are many other questions to be answered in ‘the Ruin’, as a web of lies needs to be pushed through:

- Who can be trusted?

- Are the garda (police) being effective and vigorous in their investigations?

- What is hidden in the past?

- Can Cormac Reilly uncover details from so long ago?

Author Dervla McTiernan had a legal career in Ireland before migrating to Australia with her family. Interestingly, she has tied Australia lightly into this story. Her insight into the legal system in Ireland is obvious, but depressing, if real. Cleverly, it is the twists and turns and the possibilities in ‘the Ruin’ which keep you guessing as the investigations continue. Who is really telling the truth?

For readers interested in writing (and crime fiction), there is a Writing Studio conducted by Dervla, where she discusses some of the basics of writing: https://dervlamctiernan.com/better-reading/ which is well worth a visit. With 2 more books in the Cormac Reilly series (‘the Scholar’ and ‘the Good Turn’ there is lots more on offer! It would also be interesting to listen to this as an audiobook, even just to listen to the Irish brogue… 😊

Look out for the movie which has been optioned for production too!

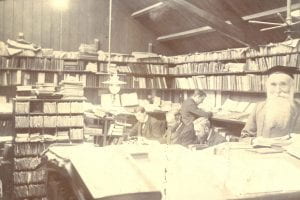

Who decides if a word is important? What should be recorded across time? Sometimes, Esme witnesses a word discarded, sees a word float below the table where the men worked as if it were unimportant – so she begins collecting neglected slips.

Who decides if a word is important? What should be recorded across time? Sometimes, Esme witnesses a word discarded, sees a word float below the table where the men worked as if it were unimportant – so she begins collecting neglected slips.

As the

As the