For Pascale, life had a predictable routine which included regular chores at home, regular teasing by his older brother and a pattern to the week. As a child in Rwanda, life was simple, but set in a loving and supportive family. He knew the happiness of running around with his friend, Henri; the pestering of a (lovable) little sister, Nadine, and the warmth of his loving parents.

For Pascale, life had a predictable routine which included regular chores at home, regular teasing by his older brother and a pattern to the week. As a child in Rwanda, life was simple, but set in a loving and supportive family. He knew the happiness of running around with his friend, Henri; the pestering of a (lovable) little sister, Nadine, and the warmth of his loving parents.

But things were set to change, as events with catastrophic impact on the country of Rwanda ignited.

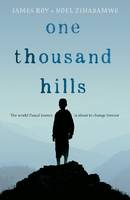

James Roy has set his novel ‘One Thousand Hills’ in April 1994, in the days leading up to, and during, the first of 100 days the genocide in which eight hundred thousand Rwandans were slaughtered. Through the eyes of Pascale, we view some of the horror and the impact of civil strife on innocents – innocents who are caught ‘hiding or running in fear’ when they should be running around in the playful games of childhood.

Through the voice of Pascale, we slowly learn of the whispers and hushed tones that alert him to something being amiss. His neighbour, Mrs Malolo released her chickens, explaining to them:

We can’t take you with us… I hope you lay your eggs somewhere peaceful and safe.

Things were even noticeably different at church on Sunday, in what was usually a joyous occasion in the week. The sermon was ominous, and afterwards people were less cordial to one another. ‘An uncomfortable heaviness hung in the air.’ Pascale notes. He also noted glances and nods between his parents, as if there was something secret they were sharing.

As a 10 year old boy, the explanation of events Pascale is able to give is cloudy, fragmented and incomplete. Interjected in between these descriptions, however, is the record of counselling sessions with Pascale as a 15 year old – a 15 year old dealing with a traumatic past. But what we read is enough to imagine the horrific times.

The ugly divisiveness of cultural differences between the Hutus and Tutsis of Rwanda is introduced in several ways, including the tearful break-up of his teacher, Miss Uwazuba and her boyfriend – ‘A Hutu Romeo and a Tutsi Juliet’. Many others with whom Pascale had friendships within his village Agabande, end up rejecting him – and slowly, with increasing uneasiness, he begins to understand the radio news about ‘crushing the cockroaches’.

In ‘One Thousand Hills’ James Roy tackles an enormous event in world history, in partnership with Noel Zihabamwe, who actually lived through these events as a ten year old. Their reasons are clear:

We wanted to tell this story because we believe it’s only by understanding the terrible and tragic events of the past that we can prevent similar events happening again in the future. (Author’s Note)

A challenging read. While ‘One Thousand Hills’ is not a happy tale, it reminds us of a bleak part of world history which has had far-reaching consequences (including two decades of unrest in neighbouring DR Congo, which have cost the lives of an estimated five million people) – something we cannot simply brush aside or ignore.

Sometimes we need to take on challenging reads like this, or those listed below. What do you think?

Further reading

Rwanda genocide: 100 days of slaughter (BBC News) explains more.

For an older (biographical) perspective on Rwanda, read:

- ‘Frida : chosen to die : destined to live’,

- ‘Emmanuel Kolini : the unlikely bishop of Rwanda’

- ‘Bishop of Rwanda’ – but be prepared for ugly and extreme reality in their stories.