There have been many books written covering the impact of World War (both I and II), but are they as touching as this one?

There have been many books written covering the impact of World War (both I and II), but are they as touching as this one?

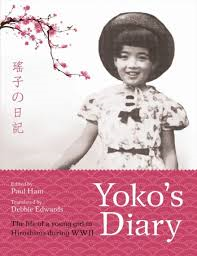

Many years after her death from the release of an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Yoko Moriwaki’s brother was encouraged to publish her childhood diary.

As a twelve year old, Yoko kept a simple diary in which she recorded daily events in her life, from the time when she was admitted to the prestigious, First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School in April 1945. It may have been a project set by her teacher, but within its young prose, Yoko has captured the essence of life for many school children in Japan at this time.

In this edition, interspersed with her entries, are explanatory notes which help the non-Japanese reader to understand many of the cultural aspects which impacted her young life – their religion, celebrations, customs and expectations of young and old. It also adds to the mundane action of daily tasks and routines Yoko kept to as a child of the 1940’s.

It is a record of a young girl, her hopes and dreams, and her feelings about life in Japan as major battles were played out both worldwide and on the homefront. Though it is a little repetitive at times, and hardly an exciting journey, it does reveal the way in which ordinary life goes on at home during wartime, both in spite of and because of wartime needs.

It also shows how, slowly, wartime rationing and the government’s efforts to rally national pride impinge on the ordinariness of her life. As school students, Japanese children were gradually employed in the war effort, to the point of clearing areas that had been bombed, and with minimal time for proper school classes,; these reducing as the war extended.

Throughout, as reflected in Yoko’s commments, students were made to think that Japan would soon win the war, and were taught to blame the American and British for all their discomforts. Yoko’s diary constantly remarks that she needed to do her best, in spite of discomforts or shortages, since it was nothing “compared to what our soldiers are going through.” She records that the deputy headmaster said: “We must work hard because the fate of our country, Japan, rests on our shoulders.”

Many of the days have similar entries.About long days of travel to and from school, along with the constant interruptions of the air raid signals. Yoko’s days are long – with home duties combined with unexpected changes to her normal routines. Visits to family, absences of her mother, anxiety about her father on the war front are all revealed through her innocent childhood diary entries.

What makes this story different are the additional explanations by the editor alluded to earlier and the trbutes to Yoko, gathered by her brother, from those who knew her at this time. Survivors reflect on Yoko, and the ordinariness of life before the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Yoko’s diary brings home the harsh reality for the innocent victims caught up in war – and hopefully gives humanity a moment to think of the need to find better ways to resolve global conflict.

Can stories such as this make a difference to our thinking? If we better understood different cultures around the globe would there be less conflict? Do such stories change our points of view?