She is only 15, but American authorities suspect she may be more than she first appears – but is Parvana really a terrorist?

She is only 15, but American authorities suspect she may be more than she first appears – but is Parvana really a terrorist?

Parvana’ Promise is the sequel to Deborah’s Ellis’s Parvana and Parvana’s Journey; books which were inspired by the author’s visit to Pakistan to help at an Afghan refugee camp. They focus on the life struggles of Parvana and her friends and family, as they face the turmoils of daily life under Taliban rule in Afghanistan.

Life as a girl in Afghanistan is particularly challenging. In past books, Parvana disguised herself as a boy in order to support her family, since the Taliban forbids girls working. Education of girls is another forbidden, as highlighted recently in real life, by the shooting of a 14-year-old schoolgirl, Malala Yousafzai, in Pakistan (for daring to oppose its rule and advocating for the right of girls to go to school).

In Parvana’s Promise, Parvana and her mother run a school for girls, and they face lots of dangerous opposition to this. This school is where she is found and apprehended by the US Military, when they bomb the school. From here, Paravana is imprisoned and questioned constantly – but she refuses to utter a word, much to the frustration of her captors.

Parvana’s story moves from the present to the past and back again, as we try to understand why she is remaining totally silent. Her strengths and loyalties shine through, though it is sometimes hard to comprehend that life could really be like this for children around the world. However, through her tale, we catch glimpses of life under Taliban rule which are realistic, given Ellis’s own experiences among Afghan refugees.

Interestingly, Deborah donated the royalties for both Parvana’s Journey and Parvana to ‘Women for Women’ in Afghanistan. A recent interview with Deborah Ellis gives an insight into how her books have come about and how she thinks as she writes. It highlights so much how good writing comes from writing about things you really know.

Parvana’s Promise has been criticised for its negative portrayal of both the US military and the Taliban, but Ellis simply wants to focus on the child’s perspective in a dangerous land. What do you think?

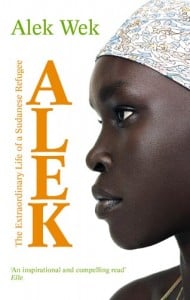

Sudanese. Poor.

Sudanese. Poor.